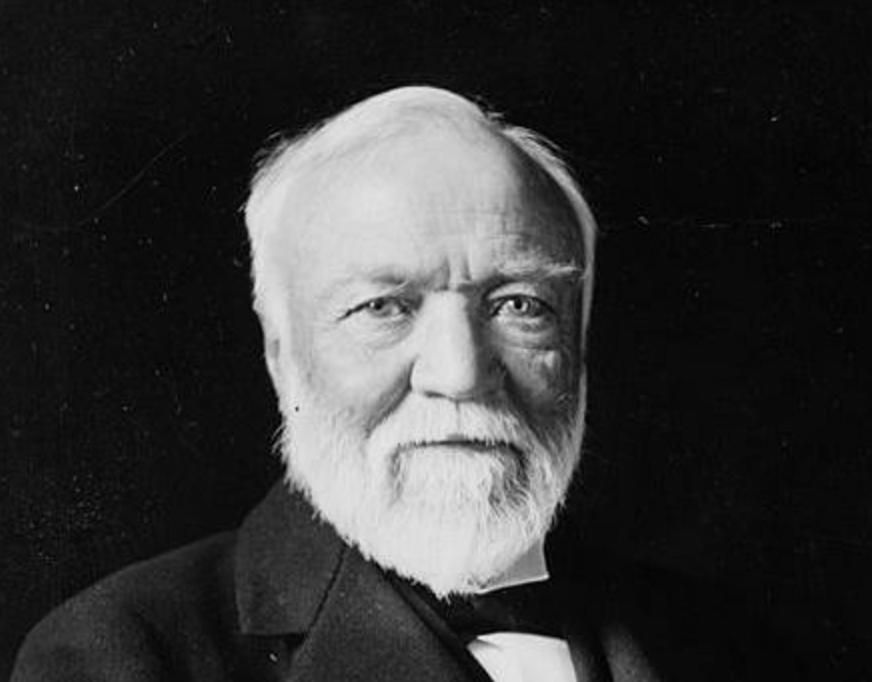

Andrew Carnegie, the father of library philanthropy, helped pay for several thousand public libraries in the United States and elsewhere.

What he did not do, however, was to relieve librarians of worries over the ongoing maintenance and stocking of the libraries.

Hundreds of U.K. libraries have closed in recent years. And the same may happen here in time, given all the new headwinds that U.S. libraries may face in the future from foes of adequate support for them.

We need to modernize Carnegie’s vision, especially in the era of ebooks and other digital content that in many cases will require ongoing sources of money.

Here in the United States, we have the right of first sale doctrine, which says books can be truly owned, meaning they can be lent endlessly, one at a time. It’s a good doctrine. But in practice, with publishers and others often insisting on other business models, first sale is far from a full solution.

If nothing else, how can libraries pay for never-ending support of electronic databases from commercial sources? Aggravating the problem is that local taxes are the primary source of money for public library books and other library resources.

Biloxi just is not going to enjoy the same funding level that Beverly Hills or Bethesda will. What’s more, the average expenditure per capita on public library collection items in the U.S. is only about $4 a year even with wealthy localities included. That is just $1.3 billion, as reported by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. School libraries, meanwhile, have been laying off well-credentialed librarians at the expense of students’ academic skills if we go by past research.

A national library endowment could at least help K-12 libraries and other kind in Biloxi and elsewhere enjoy more of the funding stability they need to survive in this new environment. Remember, by way of interest, dividends, and stock appreciation, an endowment can keep on giving.

Unfortunately, in the United States, library foundations and equivalents for public and presidential libraries total only several billion or so, just a fraction of the libraries’ operating budgets. Compare that estimate to some $36 billion just for Harvard’s endowment alone.

This is, clearly, a social justice matter. Granted, an endowment focused on donations from the super rich would come with issues of its own, such as how they amassed their fortunes. But we must keep in mind that tax money itself is hardly pure. It comes in part from massive polluters and other corporations with less than perfect morality. Besides, we should not lump together all the super rich. We can disagree with Bill Gates and Microsoft lawyers over some aspects of antitrust and on many other matters, but recognize that he is worlds apart from, say, the Koch Brothers.

MORE EFFICIENCY, TOO, AND BETTER SERVICE–NOT JUST MORE MONEY

The proposed library endowment not only could send more money in the direction of libraries of all kinds, including academic libraries, but also use technology to help them spend it more efficiently and better serve their users.

No, not everything supported should be digital, far from it; but with paper books dominating, only around 12 percent of public library spending is on actual content. The majority of the money goes for other expenditures such as librarian salaries. Does this mean we should fire librarians? Just the opposite. If nothing else, as demonstrated by Americans’ vulnerability to “fake news,” exacerbated by their reliance on social media, we need more librarians to promote useful, authoritative content.

Executed properly, a digital strategy will mean more outreach efforts, more story-telling hours, more interaction between librarians and users, and better school libraries. To understand the K-12 benefits of e-books when used well, especially for boys, see a study from the U.K. Literacy Trust. Other major research documents the rewards of recreational reading, which ebooks can encourage.

Among other things, the endowment could also help finance the creation of open access works to help drive down the prices of textbooks, which have risen 1,000 percent since 1977 and 88 percent since 2006.

AN UPGRADED WORKFORCE—AND SMARTER CIVIC LIVES

What’s more, via 3D printers and other offerings, the endowment could help whet future and existing workers’ interest in the new technology.

Countless American library-goers badly want to learn new high-tech skills, and that should jibe with one of Carnegie’s observation in Gospel of Wealth: “The main consideration” of philanthropy “should be to help those who will help themselves.”

Significantly, the endowment would be a win for the elite—the potential donors—along with workers. With a better-prepared, more prosperous workforce, the .00000001 percent would enjoy a larger market for the goods and services of the companies they owned. The rest of the country could better survive in an era when automation, not foreign competition, will be the main threat.

Moreover, ideally, if automation ends up shortening the work week of the average American, cultural and civic pursuits will count more. Or do we want the extra time to go simply for consumption of mindless videos and junky VR? Entertainment has its place. But let it not push aside other activities.

The advent of the driverless car if anything could open up more opportunities for reading and other desirable activities if society prepares through the endowment and otherwise.

Otherwise we may be left with an entertainment-fixated citizenry more vulnerable to demagoguery.

BILL GATES IS PHASING OUT HIS LIBRARY PHILANTHROPY: TIME FOR A CHANGE OF MIND?

Is the money out there, however, for an endowment to become a reality?

Librarians once hoped that Bill Gates would be their new Andrew Carnegie. Instead the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the major recipient of charitable donations from Warren Buffett, not just the Gateses, has been phasing out its Global Libraries Initiative.

This is happening regardless of the ongoing needs of libraries and their ability to complement the foundation’s work in areas such as education and public health (more literate people live longer).

Furthermore, the foundation is not eternal: “Because Bill, Melinda, and Warren believe the right approach is to focus the foundation’s work in the 21st century, we will spend all of our resources within 20 years after Bill’s and Melinda’s deaths. In addition, Warren has stipulated that the proceeds from the Berkshire Hathaway shares he still owns upon his death are to be used for philanthropic purposes within 10 years after his estate has been settled.”

Ideally the Gateses and Warren Buffett will reconsider their moral obligations to future generations further into the future. While Andrew Carnegie himself did not leave behind a library endowment per se, he wanted his education-related work to go on “in perpetuity,” and he provided for this.

“Andrew Carnegie endowed the Corporation with the bulk of his fortune, $145 million,” the Carnegie Corporation of New York says. “As of 2015, the endowment stands at $3.3 billion.” In addition, Carnegie gave his trustees “full authority to change policies or causes hitherto aided, from time to time, when this, in their opinion, has become necessary or desirable.”

Carnegie, then, very possibly would have approved of this endowment plan even if it is odds with his original fund-and-run approach for public libraries. Today’s digital technology is inherently efficient. But as noted, if we are to pay authors and other creators and content providers fairly, we need to provide for ongoing expenses such as the databases that compensate news organizations. Furthermore, in a multimedia era, especially when many books will no longer be in tangible form, we will need to try harder to keep reading on the minds of the citizenry. Libraries will have to expand outreach efforts significantly.

One bonus is that the publishing industry also could benefit along the way. For example, the same promotion of specific titles in a library context—to draw Americans to brick-and-mortar libraries and their ebook sites—could help the sales of publishers and authors since many readers would want to buy books to keep or to avoid wait periods. Not just digital books but also paper books would come out ahead. Ever the capitalist, Carnegie would have approved of those collateral benefits for the private sector.

CHALLENGES BEYOND THE CURRENT GATES LIBRARY PHASEOUT

Alas, however, beyond the Gates Foundation’s phaseout of its Global Libraries Initiative, other challenges exist at local, state, and federal levels. Cash-strapped cities must choose between funding libraries sufficiently vs. the needs of, say, police forces.

What’s more, President-Elect Donald Trump is not a heavy reader and has other priorities such as increased spending on defense and infrastructure, and he is even trying to defund the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Its current budget of $230 million is hardly enough to make up for local budget shortfalls, but in areas such as technological innovation, the future demise of IMLS would be tragic.

Clearly we need both the endowment and IMLS. If nothing else, consider that in today’s Washington, freedom of expression has been increasingly imperiled, with talk of “open[ing] up our libel laws”—hence, the current desirability of a nonprofit model independent of the federal government.

HOW AND WHY BILL GATES AND THE REST OF THE PHILANTHROPIC COMMUNITY COULD RESPOND TO LIBRARY NEEDS: MORE SPECIFICS

We cannot reincarnate Andrew Carnegie to create this independent endowment. But what major figures in the library and philanthropic worlds can do is to amass donations from a whole collection of Carnegie equivalents. This could happen even if they do not donate the same percentage of their fortunes to libraries.

Might the time have come, then, for a national library endowment summit blessed by major foundations, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation?

Ideally Gates himself could revisit library issues and help organize the summit—given the high return on investment that libraries yield socially and economically. Should he not be interested, others could step in.

But let’s hope he will care, particularly with all the new talk of massive information illiteracy among the young and among voters of all ages. If nothing else, keep in mind the Giving Pledge, organized by Gates and Warren Buffett, under which signers promise to “dedicate the majority of their wealth to philanthropy.” Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth essay went further, averring that “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

The distribution of wealth issue is the very stuff about which Americans debated so fiercely during the 2016 election, amid fears of demagogues and the end of democracy as we know it. While the endowment must not be a political organization, it can at least help narrow the chasm between the .00000001 percent and the rest of us.

Objecting to an endowment, some might say the money should come from taxes instead—that the rich are undertaxed. We fervently agree that the wealthy are not pulling their weight. The federal estate tax, for example, now targeted at individuals leaving behind more than $5.49 million and couples worth above $10.98 million, should not be repealed. Gene Sperling, once economic advisor to Presidents Clinton and Obama, has in fact said it should be raised. We agree. For that matter, to their considerable credit, Warren Buffett and William Gates Sr. and his son want heavier taxation of the wealthy. But we need to be realistic. Revenue for libraries, from all levels of government, is unlikely to spike in the near future, even with the most passionate and skillful of library advocacy.

Thanks to gerrymandering, voter suppression and a corrupt system of campaign financing, we cannot expect the composition of Congress to change sufficiently for libraries to get their full due soon in Washington. Meanwhile our libraries need the money now. Furthermore, as we have pointed out, libraries should enjoy diverse sources of funding—one protection against the possible demise of IMLS or restrictions that would compromise its mission, such as a ban on ebooks with birth control information or those advocating thoughtful but controversial political viewpoints. Under the Trump administration, our foreign aid program already is defunding nonprofits that even mention the option of abortion to the women they are helping. A private endowment could at help protect libraries against government censorship.

Of course, some might argue that an endowment increasing the percentage of private support for public libraries would cause local and state governments to reduce library funding. But the endowment could deal with this issue by relying heavily on matching grants (with allowances for poorer communities without much revenue or many well-off donors). What’s more, if localities merely shifted the burden, rather than increasing funding in the future, the endowment could make it harder for them to win grants in the future. That could be determined on a case-by-case basis. As another precaution to protect public libraries’ local ties, the endowment could accept donations only from billionaires, so as not to pre-empt Friends-of-the-Library-style efforts. Even multimillionaires would still have to contribute directly to local libraries. In a related vein, an offshoot of the endowment could help fund local library advocacy on behalf of more tax funding and more local charitable contributions.

While most public library funding would still come from nonendowment sources, the new revenue could make a major difference, especially in low-income communities; and the amount available would grow over time as the endowment grew.

THE MONEY FOR AN ENDOWMENT EXISTS: JUST A SPECK OF A SPECK OF THE WEALTH OF THE SUPER RICH

Yes, the resources exist for an endowment of $20 billion within five years and its ability to spend perhaps a billion dollars in Year Five. The Forbes’ wealth figures—for the 400 richest billionaires in the United States—showed that the top ten were together worth about half a trillion as of fall 2016.

Do the math. The half trillion could pay for more than 25 national library endowments. The total wealth of the 400 is $2.4 trillion, with their average net worth at $6 billion. Now, imagine if even just a tiny fraction of the $2.4 trillion goes for the endowment; yes, we are aware of the practical side, such as the need to retain enough wealth to invest in existing and new businesses. But a “Billion Dollar Donors Club” for the endowment could happen without the members sinking into abject poverty and without their grievously depriving their companies of capital. A club member could even spread the billion or more over the five years or ten years rather than donate everything at once. The endowment also could accept lesser amounts from the super rich.

Needless to say, some or all of the elements of the national library endowment model could work in countries other than the United States, with the U.S. endowment encouraging similar efforts elsewhere. Wouldn’t it be wonderful, for example, if the model could be used to help revivify U.K. libraries, as well as help those in developing countries?

Update, May 10, 2018: Jeff Bezos is now said to be the world’s richest man, worth more than $130 billion. In 2017 his wealth grew by about $40 billion. For a prominent academic’s perspective on Bezos and charity, see Better Ways for Jeff Bezos to Spend $131 Billion, a New York Time opinion piece by Prof. Harold Pollack of the University of Chicago.

Related: EveryLibrary.org, which helps public and academic libraries fight for adequate funding. It is a cause worth worth donating to and is not in the least at odds with the philosophy of this site—in fact, just the opposite, as shown by our interest in increasing local tax support and local contributions to public libraries.

Image credit: Here. Meanwhile, for an overview of Carnegie’s thinking on philanthropy, please view the YouTube below.